Cancer and relationships What I wish people knew about cancer

Fred J. Hegner, CPCU, FLMI

General Manager of Regional Health: Focusing on a Simple and Engaging Journey for the Insurance Customer

Publish Apr 20, 2022

The chance that you know someone who has had cancer, has cancer, or will have cancer, is quite high.

It is a widespread disease that touches millions of people –either because they themselves have been diagnosed or someone close to them has, that it is an undeniable part of life and the fabric of social relationships.

As we live longer and environmental and biological carcinogens multiply, the chance of being diagnosed over our lifetime goes up dramatically.

The disease affects anyone of any age, financial status, and gender and even animals. Being so prevalent, we should not shy away from conversations about preventing, treating, and living with cancer.

Likewise, impressive improvements in treating cancer are helping more people survive complex and once deadly diseases (there are over 120 types of cancer). In the US, the number of cancer survivors is projected to increase to 26 million by 2040 and the percentage of cancer survivors in the country living at least 5 years after diagnosis is expected to go up by 35% between 2017 and 2027.

In my work at PGH, and in my personal life, I have been honoured to meet and help people from all over the world who are going through one of the most difficult and challenging experiences. I have been privileged to see the strength and love from these individuals, their family, and support systems.

Developing relationships with patients and understanding their story, needs, preferences, expectations and desires is an integral component of care management. This includes the system around them.

Knowledge, clinical skills, empathy, and compassion are all important competences for personal care managers. Building trusting relationships and personal engagement with patients, and with their family members when patient’s ask us to engage with them, benefits everyone to have important conversations and undertake treatment and care planning. It also allows us to ensure that patient’s goals are respected and followed. We extend those attributes across the continuum of care and their medical team, following patients’ needs and requirements through their journey with PGH.

I often get questions from people about ‘How do I react?’, ‘What do I do?’ when someone they know gets the news that they have cancer. These are very valid, good questions. Below are some suggestions and tips I’ve learnt and witnessed.

Remember, there is no manual on how to react to the news or situation of cancer. The person with cancer may be going through this for the first time, and so might you. You can be alongside them, rather than taking it upon yourself. Sharing love, friendship, listening or distracting (as the need may be), bearing witness, and showing up can be a big part of their healing and support as they face the experience of diagnosis, treatment, and post-treatment.

The initial shock

Cancer diagnosis is usually a shock. Sometimes the mind jumps to questions like: Am I going to die? The answer to this depends on whether it is a treatable cancer and survival rates are high, the stage of disease at diagnosis, and access to effective treatments and medical teams. Will I lose a part of my body (like a breast or leg) or physical function? Is the diagnosis correct? What do I do? Will I lose my hair? How will my life change?

The actions that follow usually include emotional processing, gathering of professional opinions and information on next steps and available treatments, confirming that the diagnosis is correct, understanding the disease, and the risks and effects of treatments. Socially, one must decide how much to share with wider personal and professional networks and undertake arrangements to support oneself throughout treatment and recovery in practical, emotional, and psychological ways.

Living with cancer

During and after therapy, people continue to live their lives and fulfil their roles as family members, students, or workers. Sometimes the cancer comes back, and they go through treatment again, experiencing once more the full range of emotions and feelings that can accompany cancer diagnosis.

What should friends and family remember?

Many times, I hear people with cancer say that they wish people were more aware of the following things about cancer:

• Cancer is not a death sentence. Although, we associate cancer with death, the chances are high that people have been – and are – living with cancer since their diagnosis for 2 or more years. Getting cancer and undergoing treatment is only one part of living.

• Cancer is a diagnosis for an entire family and support group. It affects everyone around the person diagnosed. It can change friends and family for both the worse and the better.

• Life can change at any point. We have this misconception and misinformation as a society that it will not happen to me or to someone close to me, that we are too young, too strong, too active, or too lucky. But sometimes life can flip upside down at any time. Instead of shying away from the conversations and visibility, which we can have a tendency to do – some cancer patients and survivors demand that we talk about getting and surviving cancer in its full dimensions, be prepared, and be ready to have these conversations.

Reactions from friends and family to a diagnosis of cancer

Responses from friends and family tend to fall everywhere on a wide spectrum. On one end of the spectrum, there are those that are not ready to deal with the news and don’t want to know anything about the person. They might even ghost the patient or disappear, which can feel like abandonment. On the opposite end, there are many people who reveal themselves to be unconditional and are there for patients every step of the way.

Mostly, people fall somewhere in the middle — wanting to be there for the patient because they sincerely care, but they don’t know how. These friends alternate between not wanting to seem careless, but not wanting to overstep.

What to do and not do

If someone you know has been diagnosed with cancer and is sharing this news with you, don’t be afraid to share statements of support and ask what they need.

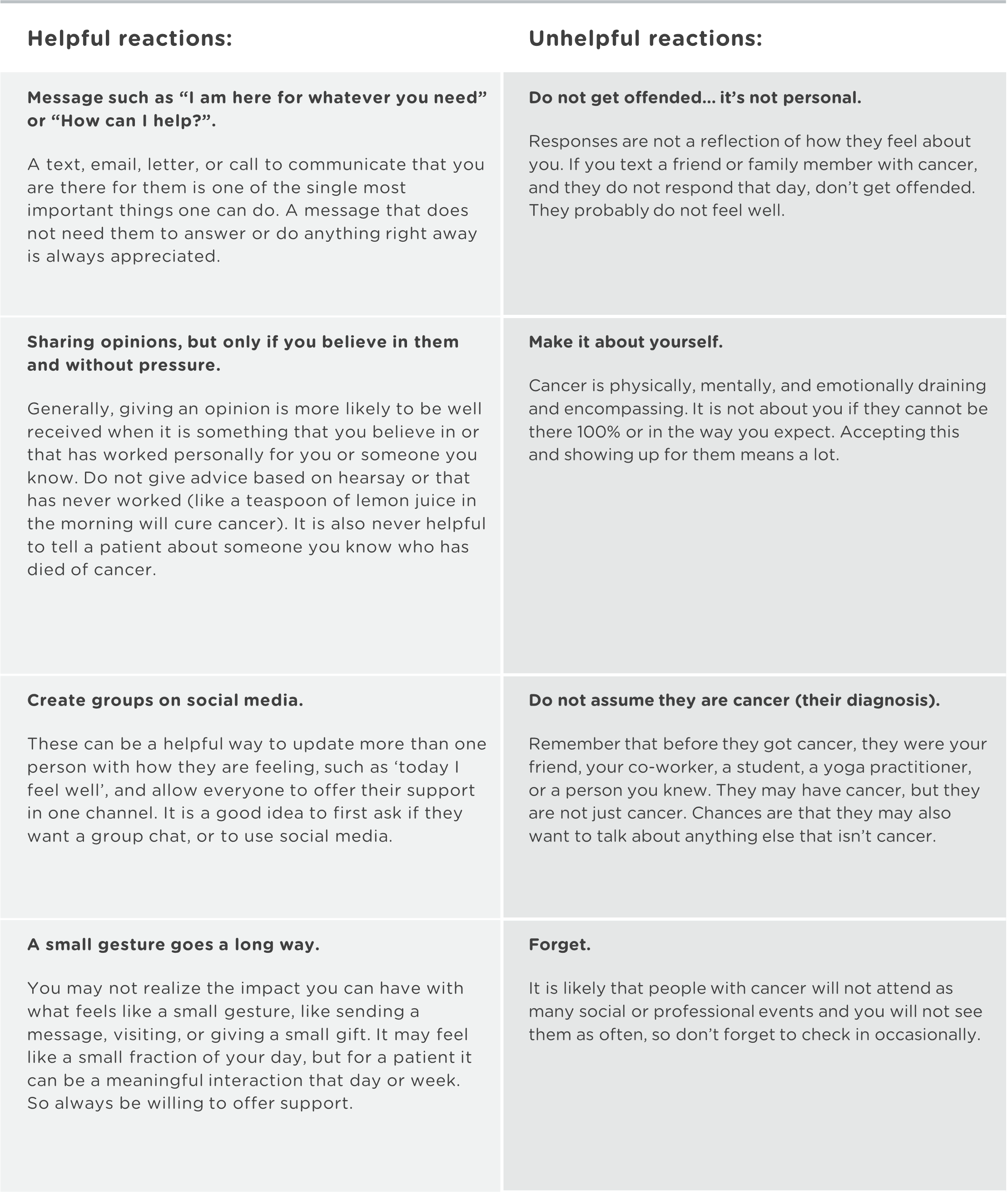

The following are some tips of responses that may be appreciated by people facing cancer and some that probably will not.

Some Things to Expect

Be willing to unlearn and learn some ways of seeing and being in the world:

1. A relationship cannot be 50/50. A relationship with someone going through cancer cannot be completely equal. This goes for other things besides cancer, such as mental health or grieving. They are not ‘using cancer as an excuse’ or being a victim. Although it may seem unfair, they need energy, focus, and support to heal.

2. It’s OK to have bad days and it’s OK to ask for help. People sometimes believe they have to remain positive and strong and do everything on their own; for themselves or for others. It’s ok to lie down, ask for help, not do things, and to feel all types of emotions.

3. People come in and out of our lives. Sometimes people show up for a someone they know with cancer, and sometimes they do not. It helps to not hold grudges or be resentful towards those who do not show up, but just appreciate the fact that during a period of life you were together, learning and growing.

Silver Linings

1. Love and Friendship. While going through challenging periods in life, we often get the gift of seeing those people who are there for you and feeling how much they love you.

2. Gratitude. When confronted with illness, one stops taking things for granted. Because the disease disrupts so many things, one learns a lot about being grateful. Everyone has bad days, even if you don’t have cancer. Even when you are not looking forward to something ahead, it helps to practice gratitude, no matter how small, for what you have or who you are, and appreciate that every moment is different to the one before.

3. Acceptance. It is also easy to reject negative emotions and want very hard to be positive. This is the opposite of acceptance. A gentle way is to acknowledge the negative, without criticizing or judging, denying, beating yourself up, or trying to will yourself into being grateful and positive because it’s what you think you should do[1]. Taking ‘shoulds‘ out of the vocabulary helps.

4. New people and new perspectives. In responding to cancer, people often undergo many new experiences and encounter new people and perspectives. For example, in addition to western science there is a lot to learn from other healing methods from other cultures.

5. Empathy and Forgiveness. Everyone is going through something; whether it is a disease, a loss, pain, or insecurity. We have no way to know for certain what someone else is experiencing, but we can be more empathetic and forgiving and listen and pay attention.

I have been a part of the resilience, compassion, anger, sadness, hope, love, determination, and commitment of patients, doctors, care managers, and friends and family who are facing cancer.

Their experiences before, during, and after treatment, and the vast improvements in science and research give me hope that one day we will have a cure for cancer. In the meantime, we get to learn and appreciate life in all its complexity and experiences. As we acknowledge those of us living with or having cancer amongst us, we can better understand the disease and support each other through and after.

Sources:

- “Study cancer survivors”. Nature568, 143 (2019).

[1] Jiddu Krishnamurti, a 20th century Indian philosopher, explained the difference between introspection and acceptance as introspection being akin to self-analysis and a means to understand and to change something. For example, to be different, or to attain something you want, such as be less angry or more kind. When you fail at changing and the end is not achieved – from the point of view of the observer, the ‘I’ – then frustration and depression might arise. Acceptance, awareness, are different in that it is observation without condemnation, justification, or identification. Acceptance is looking at what is, without categorizing, trying to shift or change it, judge it or expect something. The magic is that there is transformation, and movement and change in acceptance.